Is this the worst car in Australia's history?

The story behind one of our greatest motoring mistakes.

So there’s good news and bad news.

The good news is that you’re in for a short week.

The bad news is that between now and Friday you’re likely to be subjected to Australia Day opinion pieces whether you want them or not. Personally, I have already reached my limit. I’d rather eat glass than hear one more word about supermarkets selling Australian flags.

But — alas — there’s probably a right wing commentator typing up an op-ed on this topic right now. Sitting at his desk, tapping away at his keyboard while simultaneously having an angry wank.

Tap, tap, tap. Wank, wank, wank. Pause to glower in mirror. Wank, wank, wank. Tap, tap, tap. Repeat until shameful completion (of the op-ed).

Now, some people will say that there shouldn’t be anything political about a car website. Which is totally fair. Sometimes you want to turn off your brain and car stuff is probably a good place to come for that.

Let’s be honest. This isn’t always a thinking-person’s area of interest. The Summernats festival earlier this year made that abundantly clear.

So instead of tackling the tricky and nuanced issue of Australia Day, I’ve decided to take a look back through the archives. This week I’m presenting you with a story about what could be the worst car ever built in this country.

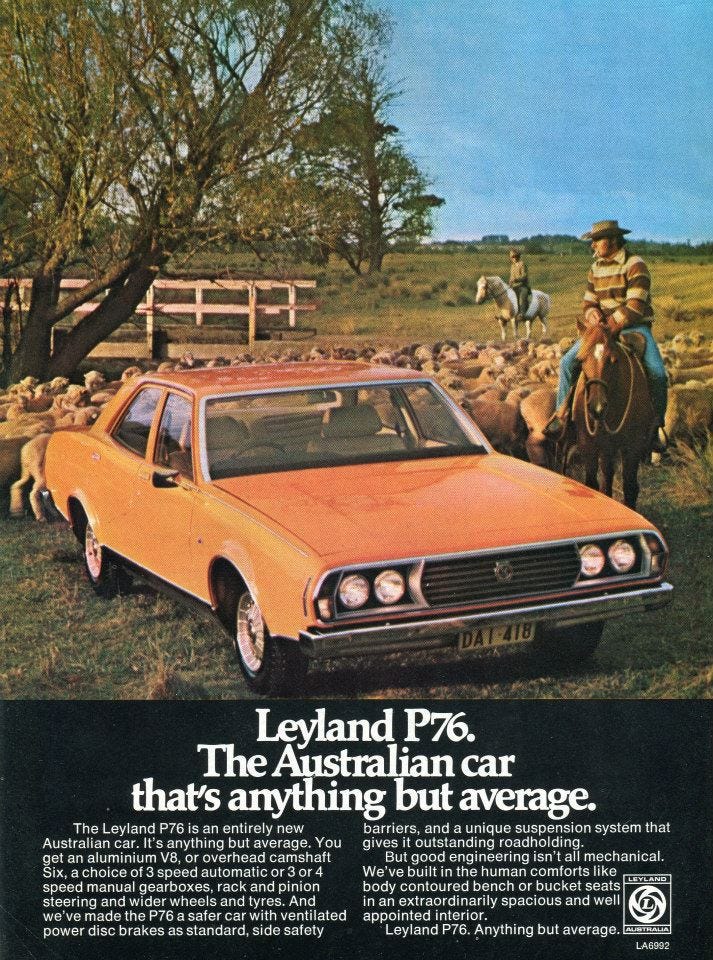

The Leyland P76.

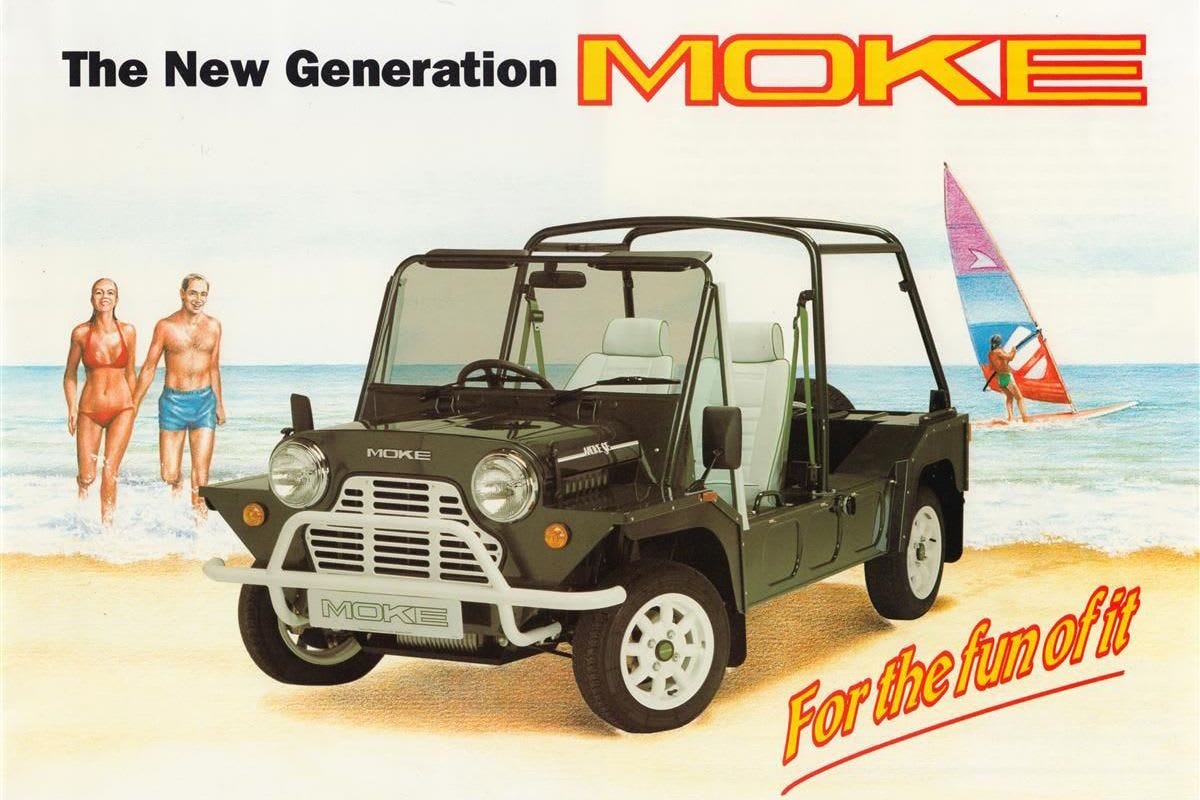

In the late 1960s, you could say that car manufacturer Leyland was going okay in Australia. They’d had success with the Mini and the weird-but-cool Mini Moke. But these were smaller vehicles and Holden and Ford had shown Australians had an appetite for big cars.

You might ask: what constituted a big car in the 1970s? Was it ride height? Width? The number of passengers you could drive?

No.

It was the ability for a person to fit an entire 44-gallon drum in the boot.

Well, that was according to Leyland, anyway. Depending on what you read, this was a specific requirement given to the design team.

I wish car makers used similarly irrelevant items to show scale today. Don’t tell me how many litres the boot has. Instead tell me how many mid-sized shetland ponies, boxes of Monopoly, or Barbie Dream Houses I can shove in there.

Anyway.

While being able to fit a 44-gallon drum in the boot was a lofty goal (I guess), Leyland’s designers made it happen.

And sure the disproportionately large boot made the car ugly – but think of all those enormous drums people could now transport! The Australian public’s screaming demand to move 200-litres of liquid from one location to the next finally had an answer. And that answer was the P76.

Happy with their totally normal boot decision, the final designs were signed off by executives, and the P76 was put into production. Before long cars were rolling out of Leyland’s Zetland factory.

In the beginning things seemed to be going well. There were more than 2000 orders in the first week. Wheels magazine even named the P76 as their 1974 car of the year. To be fair, when you ignored the aesthetics, there was much to be admired about this car. It was lighter, more powerful, and had better brakes than the competition.

Unfortunately, things became unstuck when people got behind the wheel.

Poor seals meant the car was uncomfortably draughty and the interior would get wet in the rain. On the bright side, if you had the V8 model, the carpets would quickly dry out thanks to the poorly-insulated, overheating exhaust. But unfortunately, things would get so hot the carpet would then start smouldering.

Oh and the rear windows would sometimes just fall out. Just because.

We take car reliability for granted these days, but even by the dubious standards of the 1970s, the Leyland P76 was a lemon.

With enough time and money, perhaps these problems could have been overcome. But there were other factors at play.

The P76 was a big, thirsty car which was launched in the middle of a fuel crisis when people were looking for vehicles which were more economic to run. This, along with increased competition, new unfavourable Government policies, and difficulties with Leyland’s unionised workforce made the P76 untenable. It was pulled from the market after just 16 months.

The whole venture ended up being a $50 million loss which resulted in Leyland pulling the pin on their Australian car manufacturing division.

On paper and in boardrooms the Leyland P76 was a good car at the right time. But when the finished product finally reached the market, things had changed. For all their good intentions Leyland had made a bad car which didn’t suit the country Australia had become.

These moments can, in some form or another, happen to us all. When they do occur, it’s okay to stop, take stock of things, and change. That’s true for whether you’re a car manufacturer, an individual, or – say – an entire nation grappling with a divisive public holiday.

Not that this is a very tenuous allegory or anything.

Enjoy the extra time off. I’ll see you next week.