How the mushroom murders brought Australia together

It’s not what Erin Patterson meant to do, but it’s what happened.

Every now and then, the Australian media is blessed with a truly plenteous story. One which has every management-dictated target for views, clicks, or downloads easily exceeded. A hungover journalist need only sneeze out a tangentially-related listicle and reap the bounty.

In these good times, the fair weather seems as though it will stretch on forever, so hay is made, and made, and made until there are no more fields to clear.

Erin Patterson – who murdered three members of her ex-husband’s family with beef wellington laced with poisonous mushrooms – has been such a story.

The public can’t get enough. They’re insatiable. Like geese who’ve volunteered for gavage, they fatten themselves daily on think pieces, photo albums, news articles, and television stories, piped directly down their gullets.

Perhaps you think this comes off as glib. We’re talking about a murder, after all. Three people were killed in the most calculated and callous manner. That is a tragedy, no mistake.

But it’s just you and me here. So turn your Bachelor of Arts degree around to face the wall, stop moralising for a moment, and be honest. Have you noticed there’s a jocular, almost festive, tone to the conversations about this case?

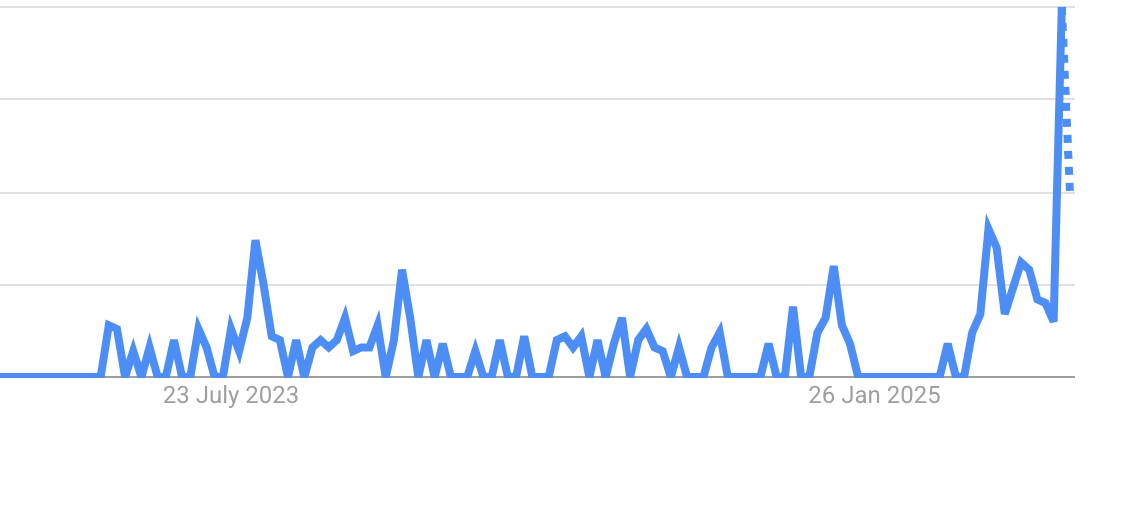

There have been off-colour jokes about Patterson ricocheting around the country since before she was charged. The question “do you think she’ll get off” has sustained hours of office chatter. Even beef wellingtons are having a renaissance – Google searches for recipe have exploded since the case has been in court. It’s a crowd-pleaser at a potluck, and a conversation starter, too.

So what makes this story so popular, and why does it seem to be bringing people together? I think there are a few things at play here.

Firstly, to have touched a book is to see the profound human drama of this case. It’s Shakespearean. Family intrigue, plots, betrayal, murder and poison – Hamlet and Patterson’s ex would have much to bond over at the pub.

Humans are primed for interesting stories. Our bodies might be made of atoms and molecules, but our humanity is formed from parables and fables. Before we can talk, we’re fed tales that teach us what is fair, what is right and wrong, and what happens to the people who transgress those expectations. They are comforting in their easy lessons any black-and-white justice.

But then you grow up and realise that life doesn’t have tidy beginnings, middles, and ends. Truth is hard to define, and morality even harder.

Where is the Little Golden Book on the man who murdered the evil health insurance CEO, and does it say whose side I’m supposed to come down on? Or Hans Christian Andersen stories on whether violent protests are acceptable in the face of extreme injustice? Did Aesop ever write about the Gaza?

We were not adequately equipped for the relentless complexity of modern human life.

Then Erin Patterson enters the picture. We’re told she invited family over for dinner and served them poisoned food which killed three people. Yes! This one is easy! What she did is bad! We can all agree it’s bad and that’s a relief. Even better, she is found guilty and put in gaol. Justice is served, and we all learn a lesson that killing people has consequences, and that we shouldn’t trust spiteful exes to feed our family.

But beyond the fundamentally compelling nature of the story, the Erin Patterson case achieved something else. It became a common interest shared by much of the country.

Briefly, Australia was a monoculture once again.

This used to be the norm. We had fewer options, so people around the nation would watch whatever was on the television — all five channels of it – and then talk about what we’d seen the next day.

It sounds so banal. Many people probably didn’t even notice the gradual erosion of this common ground as we moved from televisions to computers, computers to phones. But it disappeared all the same, and now there is a void.

Cultural touchstones have been replaced with fleeting online trends that blip in and out of existence like distance stars on the horizon. They have no enduring legacy, and we have a compromised memory anyway.

This all seems like a small price for the largess of the payoff. We never, ever have to be bored ever again. Entertainment based on your specific interests will be delivered in precisely the manner you’ll enjoy the most.

But that doesn’t mean I’m interested in what you’re interested in.

You might like Joe Rogan, for example, but I would rather gnaw off my own hand than hear about it. Equally, I would love to talk about the four hours of Robot Wars I watched last night. I could wax lyrical about which killer robot built by nerds has the best weapons, and the most devastating wipeouts. But I realise that might not be a universally enjoyed conversation (not that this always stops me).

As our most obscure hobbies and preferences are indulged in small online communities, we lose topics of general interest with the people we interact with in person. It’s hard to quantify what the social implications of this are.

Shared pop cultural experiences are an older phenomenon that you might think. Charles Dickens, for example, released much of his work in serialised form – several chapters published every month in newspapers. It’s said that in Boston and New York, crowds would gather at the dock when they heard new chapters were due to arrive on ships.

This isn’t just common ground, it’s also neutral ground. We sorely need more of it. In a politically divided world, it’s harder to find timely topics that everyone can converse about amicably. Who’d have thought that a vicious premeditated murder would briefly give Australia this gift.

Of course, none of this is what Erin Patterson set out to achieve. She just wanted to kill as many of her in laws as possible, and then get away with it. Australia was both appalled and enthralled. We were, briefly, brought together in our morbid fascination.

I suppose these days we must take whatever moments of unity we can get.

A newsletter about unity, then spelling it gaol. What a ride.

Truly! I felt awful trivialising it when people have died but she did seemingly such a bad job of it, that it was hard not to talk about it! The white jeans, the dehydrator, the mushroom groups. Like Erin, girl, if you’re gonna represent women on the world stage of murdering, DO BETTER.